A new study from the Stanford School of Medicine revealed shows that diet rich in fermented food maintain gut health and lower signs of inflammation at molecular level.

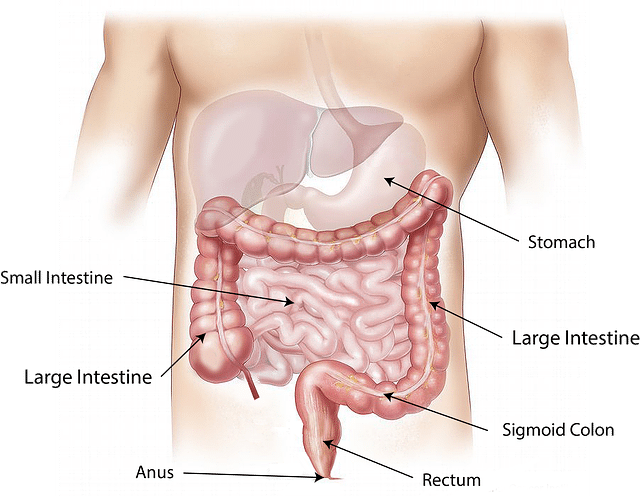

The human gut provides a home to over 100 trillion microorganisms collectively known as microbiota, which perform fundamental roles in many aspects of human biology, including metabolism.

However, the diet we consume changes the structure and activity of the microbiota (David et al., 2014), modulating a host of effects on our health (Clemente et al., 2012). Does the altered gut microbial diversity affect immune response?

The Study

In a clinical trial, humans have been randomly given two different types of diets. One group received a diet rich in fermented foods, while others consumed a diet high in fiber content. Assessing the impacts of diets on health, the researchers found that the diet changes the diversity of gut microbiota and inflammatory molecules.

The reasons for focusing on only high fiber and fermented foods were previous reports, wherein consuming fermented food was shown to associate with weight management and decreased risk of diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. On the other hand, high-fiber diets have been described as positively impacting lowering mortality rates (Park et al., 2011).

In their study, the researchers examined blood and stool samples collected during a three-week pre-trial period, the ten weeks of the diet, and a four-week post-trial period when the participants ate as they chose.

More Read

Outcome

They found that participants who consumed a diet rich in fermented food showed steadily increased gut microbiota diversity and decreased inflammatory markers. On the other hand, the high-fiber diet participants had increased microbiome-encoded glycan-degrading carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) despite stable gut microbial diversity.

The study results are now published in the journal Cell (Wastyk et al., 2021).

Eating fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, kimchi, kombucha tea, and vegetable brine drinks increased overall gut microbial diversity; the larger the serving, the greater the impact.

“This is a stunning finding,” said Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology. He continued, “It provides one of the first examples of how a simple change in diet can reproducibly remodel the microbiota across a cohort of healthy adults.”

On the other hand, none of the 19 inflammatory molecules decreased in participants who consumed a high-fiber diet rich in seeds, legumes, nuts, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. On average, the diversity of their gut microbiota also remained stable.

After examining the immune response, the study found that participants in the fermented food group had less activation of four types of immune cells. At least 19 inflammatory marker proteins in blood samples decreased. Interleukin 6 (IL 6) was one of those markers linked to rheumatoid arthritis, Type -2 diabetes, and many chronic stresses, including severe COVID-19 cases.

Consuming a fiber-rich diet is known to slow down digestion, lowering the absorption of calorie-rich components, and helping the stool pass more quickly through the intestine. It also helps to lower cholesterol and increase weight loss, providing beneficial effects in protecting against coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

“We expected high fiber to have a more universally beneficial effect and increase microbiota diversity,” said Erica Sonnenburg, a senior research scientist. He adds, “The data suggest that increased fiber intake alone over a short time period is insufficient to increase microbiota diversity.”

More Read

Future Research

The researchers now aim to carry out further studies in animals to investigate how diets change the microbiota and reduce inflammatory markers. They also want to examine if high-fiber and fermented foods synergistically influence humans’ microbiomes and immune systems.

Another goal of conducting a further study is to examine if fermented food consumption decreases inflammation or changes the level of other biological markers in patients with metabolical and immunological diseases. Also, the researchers plan to investigate the impact of the prototype diet on pregnant women and the aging population.

“There are many more ways to target the microbiome with food and supplements, and we hope to continue to investigate how different diets, probiotics, and prebiotics impact the microbiome and health in different groups,” said Justin Sonnenburg.