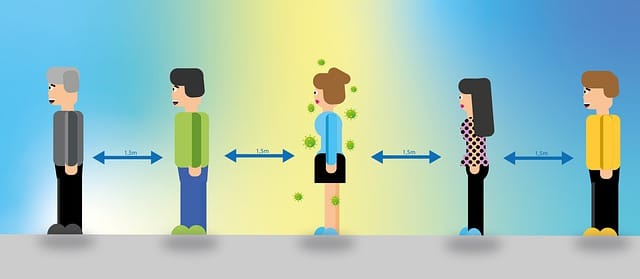

Maintaining strict social distancing is associated with a lower risk of testing COVID-19 positive. Conversely, participating in a place of worship, using public transportation, or traveling around are associated with a higher risk of Covid-19 infection—suggests a study published online in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases (Clipman et al., 2020).

For the analysis, scientists at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health randomly surveyed more than 1,000 people in Maryland in late June. They found that participants reporting frequent public transport use were more than four times as likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. In contrast, those who reported practicing strict outdoor social distancing were just a tenth as likely to report ever being SARS-CoV-2 positive.

As of September 10, 2020, more than 28 million people globally and over 6.5 million in the USA are infected by the coronavirus (Worldometer 2020). Of the total infected people, more than 900,000 people have died so far. Since no vaccine is available yet, only non-pharmaceutical interventions such as wearing masks, maintaining social distance, or staying home are the options available to curb the infections.

Despite taking measures to curtail the virus’s spread, SARS-CoV-2 infected more than 113,000 people in Maryland, and nearly 3,700 confirmed deaths, according to the Maryland Department of Health.

A growing number of reports indicate that a disproportionately higher rate of infections, case severity, or mortality among Black in the USA is primarily due to the differences in social distancing and movement. Reports show that Black communities are disproportionately high in nine vital occupations that increase their exposure to SARs-CoV-2 (Rogers et al., 2020).

In the study, the researchers included 1,030 people living in Maryland, from June 17 – June 28, 2020, using Dynata (https://www.dynata.com), one of the largest first-party global data platforms.

The researchers asked the survey participants questions about recent travel outside the home, their use of masks, social distancing and related practices, and any confirmed infection with SARS-CoV-2 either recently.

The researchers found that when considering all the variables, they could evaluate that spending more time in public places was strongly associated with having a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

For example, an infection history was about 4.3 times more common among participants who stated that they had used public transportation more than three times in the prior two weeks, compared to participants who stated they had never used public transportation in the two weeks.

An infection history also was 16 times more common among those who reported having visited a place of worship three or more times in the prior two weeks, compared to those who reported visiting no place of worship during the period.

Conversely, those who reported practicing social distancing outdoors “always” were only 10 percent as likely to have a SARS-CoV-2 history than those who reported “never” practicing social distancing.

Author’s Comments

“Our findings support the idea that if you’re going out, you should practice social distancing to the extent possible because it does seem strongly associated with a lower chance of getting infected,” says study senior author Sunil Solomon, MBBS, PhD, MPH, an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School Medicine.

“Studies like this are also relatively easy to do, so we think they have the potential to be useful tools for identification of places or population subgroups with higher vulnerability.”

“We did this study in Maryland in June, and it showed among other things that younger people in the state were less likely to reduce their infection risk with social distancing–and a month later a large proportion of the SARS-CoV-2 infections detected in Maryland was among younger people,” says Solomon.

“So, it points to the possibility of using these quick, inexpensive surveys to predict where outbreaks are going to happen based on behaviors, and then mobilizing public health resources accordingly.”

Solomon and his team are now conducting similar surveys in other states and are studying the surveys’ potential as predictive epidemiological tools.