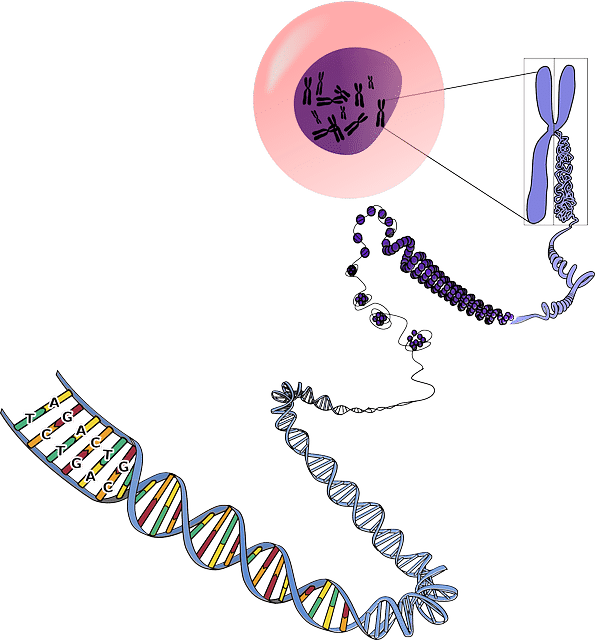

According to the outcomes of a new study headed by academics from UCL, a collection of genes that plays a crucial part in the creation of components of our cells might also affect the human lifespan.

“We have already established from extensive previous research that blocking certain genes involved in creating proteins in our cells can lengthen longevity in model organisms such as yeast, worms, and flies,” stated Dr. Nazif Alic, a co-lead author from the UCL Institute of Healthy Ageing. However, it has been shown that ribosomopathies, a group of developmental abnormalities, can result from the loss of activity in these genes in humans.

“Here, we have observed that blocking these genes may also increase longevity in people. This may be because they are most beneficial early in life before beginning to cause difficulties in later life.”

The researchers believe that as we age, we may not require as much of the effect these genes have on us because they are engaged in the machinery our cells use to synthesize proteins, which is a process necessary for survival. The genes are an example of the phenomenon known as antagonistic pleiotropy, which occurs when genes that reduce our lifespan are selected for in the process of evolution if they aid us early in life and when we are delivering children.

We have found that inhibiting genes that cause disease like ribosomopathies may also increase longevity in people, perhaps because they are most useful early in life before causing problems in late life.

Nazif Alic

The genes have been shown to lengthen lifespan in smaller species in the past, such as letting fruit flies live 10% longer, but in this work, for the first time, researchers have established a link in people as well, as they write in a recent publication published in Genome Research (Javidnia, Cranwell et al. 2022).

The researchers analyzed the genetic information from previous studies that included 11,262 individuals who had lived extraordinarily long lives, reaching an age greater than the 90th percentile for their cohort. They discovered that those with lower levels of activity in particular genes had a greater likelihood of living very long lives. Pol I and Pol III are the RNA polymerase enzymes responsible for ribosomal and transfer RNA transcription. These genes are also associated with the expression of ribosomal protein genes.

The researchers discovered evidence that the effects of the genes were linked to their expression in particular organs, such as abdominal fat, the liver, and skeletal muscle. However, they also discovered that the effect on longevity went beyond just associations with any particular age-related diseases.

These results add to the mounting body of evidence suggesting that immune regulators like rapamycin, which inhibits Pol III activity, and similar drugs may aid in extending healthy life lengths.

“Aging research in model species, such as flies and humans, are frequently different initiatives,” stated Professor Karoline Kuchenbaecker from the UCL Genetics Institute. This is where we are working to make a change. We are able to perform experiments on flies to modify genes related to aging and examine underlying mechanisms. However, our ultimate goal is to comprehend the processes involved in human aging. Combining the two areas of study by applying techniques such as Mendelian randomization provides the potential to overcome the obstacles present in both areas of study.

Both the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and Wellcome provided financial support for the study.