Excessive red meat consumption causes genetic mutation increasing cancer-related mortality in patients with colorectal cancer.

Researchers at Harvard Medical School found that processed red meat contains some chemicals known as carcinogens that cause DNA damage in patients with colorectal cancer—the findings are published in an AACR journal Cancer Discovery, this week (Gurjao et al., 2021).

In several previous studies, researchers have shown that red meat causes the induction of cancer cells in the colon, but how the meat was causing the cancer was debated. Not all researchers were convinced if there were any strong association between the two.

For example, in 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) report concluded that consumption of processed and red meat increases the risk of developing colorectal cancer (Bouvard et al., 2015).

On the other hand, a group of researchers in 2019 argued that there exists only a “low” degree of certainty that reducing red meat consumption would prevent cancer deaths (Johnston et al., 2019).

The previous research, primarily based on epidemiological survey data, has linked the association, higher the red meat consumption, the greater was the incidence of colorectal cancer and heart disease.

However, studies in experimental animals have suggested that red meat intake may induce the formation of harmful chemicals with carcinogenic properties in the colon.

But, a direct molecular mechanism to the development of colorectal cancer in humans has not been shown, Giannakis, the study’s lead author, explained.

Study Design

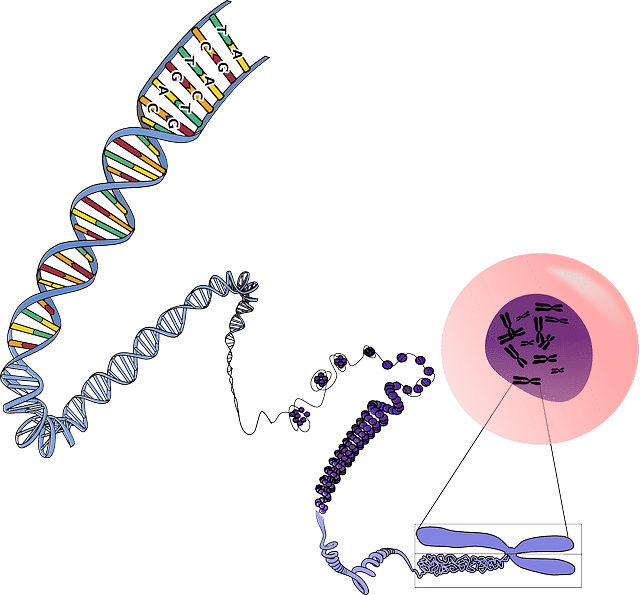

Cancer has long been known as a genetic disease. UV, cigarette smoking, and many other harmful chemicals have been shown to cause genetic mutation in normal cells, changing cell division and tissue growth.

Researchers first collected both normal (free of cancer) and tumor tissues from 900 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer to investigate if red meat consumption is associated with genetic changes.

After extracting DNA from all samples, they performed sequencing analysis on Illumina HiSeq 2000 instruments.

All participants disclosed their dietary habits and lifestyle choices for several years before their colorectal cancer diagnoses.

Major Findings

Sequencing data revealed alkylating DNA in both normal and cancerous colon tissue, showing gene mutation. Also, the degree of alkylating in the DNA was significantly associated with processed or unprocessed red meat intake.

However, no such evidence did the researchers find from poultry or fish product consumption, nor with lifestyle factors.

Also, red meat consumption was not associated with any other DNA damage identified in this study.

The researchers found that normal and cancerous tissue from the distal colon —the lower part of the bowels where past research suggested colon cancer linked to red meat mainly occurs—had significantly higher alkylating damage than the tissue from the proximal colon.

They also identified the KRAS and PIK3CA genes as potential targets of alkylation-induced DNA damage.

The study revealed that participants with the highest level of alkylating DNA damage had a 47 percent greater risk of colorectal cancer-specific death than patients with lower levels of damage.

Author’s Opinion

For the first time, this study identified an alkylating mutational signature in colon cells and linked it to the occurrence of colon cancer due to the consumption of red meat, stated Marios Giannakis, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in a press release.

“These findings suggest that red meat consumption may cause alkylating damage that leads to cancer-causing mutations in KRAS and PIK3CA, thereby promoting colorectal cancer development.”

The data further support the idea that red meat intake is a risk factor for colorectal cancer, the authors mentioned. “The finding also provides opportunities to prevent, detect, and treat this disease.”

Study Limitations

Participant selection is the potential bias of this study, as the researchers were unable to collect tissue samples from all colorectal cancer cases in the cohort.