A groundbreaking PNAS study from the University of Washington researchers suggests that a simple blood test might be able to identify people at risk for developing Alzheimer’s before their memory and cognitive function is affected.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, a neurological disorder that affects cognition, memory, and behavior. It is a progressive and degenerative disease with no known cure and is characterized by the buildup and deposition of toxic proteins in the brain. AD affects 5 million Americans and over 50 million people in the world.

Now, a groundbreaking study suggests that a simple blood test might be able to identify people at risk for developing Alzheimer’s before their memory and cognitive function is affected.

According to the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a team led by University of Washington researchers have conducted a series of experiments on AD patient and noncognitive impaired control (Shea et al., 2022).

The study has discovered that a toxic protein called amyloid-beta (Aβ) could be detected in blood samples taken from people with Alzheimer’s disease and in samples collected from people at risk of developing AD.

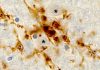

This protein is associated with the early onset of cognitive impairment in people with the disorder. The Aβ proteins misfold and clump together, generating tiny aggregates known as oligomers. Those “toxic” oligomers of amyloid beta are expected to grow into Alzheimer’s disease over time, in a mechanism that scientists are still trying to comprehend.

The blood test, called SOBA, could identify oligomers in Alzheimer’s patients but not in most control group members who exhibited no cognitive impairment at the time the blood samples were obtained.

However, SOBA did detect oligomers in the blood of 11 control group members. Ten of these people had follow-up examination records, and all were eventually identified with moderate cognitive impairment or brain pathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease. SOBA found harmful oligomers before symptoms in these 10 people.

“What physicians and researchers have desired is a reliable diagnostic test for Alzheimer’s disease that both confirm a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and identify indications of the illness before cognitive impairment arises,” said senior author Valerie Daggett, a UW bioengineering professor. “We illustrate here that SOBA might serve as the foundation for such a test.”

SOBA (soluble oligomer binding assay) takes advantage of a unique characteristic of toxic oligomers. When misfolded amyloid beta proteins aggregate into oligomers, they produce an alpha sheet structure. Alpha sheets are uncommon in nature, and a previous study by Daggett’s team showed that alpha sheets tend to attach to other alpha sheets. SOBA is built around a synthetic alpha sheet created by her team that can bind to oligomers in cerebral fluid or blood samples. The test subsequently confirms that the oligomers adhered to the test surface are formed of amyloid beta proteins using established procedures.

SOBA was evaluated on blood samples from 310 study patients who had previously provided blood samples and portions of their medical information for Alzheimer’s research.

SOBA can detect oligomers in the blood of people with mild cognitive impairment and moderate to severe Alzheimer’s patients. The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease was confirmed after death by autopsy in 53 individuals, and toxic oligomers were found in blood samples collected years before their deaths in 52 of them.

According to data, SOBA also found oligomers in control group participants who eventually acquired minor cognitive impairment.

The study findings are groundbreaking, as they could help identify those at risk of developing Alzheimer’s much earlier, thus allowing them to benefit from early intervention, better care, and support, as well as treatments that could help slow down or even halt the progression of the disease.

The researchers acknowledge that more work needs to be done to solidify the link between high levels of Aβ and Alzheimer’s, as well as further explore the potential of using a blood test for early detection. Nevertheless, these findings take us a step closer to our goal of halting the devastating progression of Alzheimer’s and offer hope for those suffering from the disorder.

Daggett’s team is collaborating with scientists at AltPep, a UW spinoff firm, to turn SOBA into an oligomer diagnostic test. The researchers also demonstrated that SOBA could be easily adjusted to identify hazardous oligomers of another kind of protein linked to Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia.